Heart of the Comet Read online

Page 4

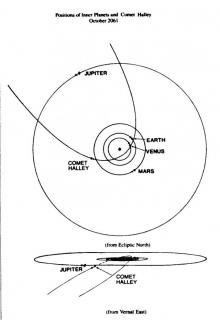

Spacer Second Class Otis Sergeov had never appeared particularly disabled by his handicap. In fact, it seemed to make him quicker in microgravity. She had heard that Sergeov was now assigned to helping Joao Quiverian and the other astronomers studying Comet Halley.

He was the oldest Percell Virginia had ever met.

Being one of the first had its drawbacks. Simon Percell’s famous early work in genetic surgery had made it possible for Sergeov’s parents to have children at all. But a mosaic flaw had left him with only small nubs below his shorts.

“Oh, hello, Otis,” she greeted him. “Something has to be done about this. Has anyone reported it yet?”

The Russian spacer shrugged. “Is doing what the hell good, reporting thing like this? Nobody does nothing about it, for sure,” he groused bitterly in mixed Russian and English. “The Stchakai cretins!”

Virginia blinked at the apparent nonsequitur. Of course Captain Cruz would order repairs at once, when someone told him ....

Then she noticed that Sergeov wasn’t even looking at the lubricant leak. Virginia rode the slowly rotating hub until she was even with the man, then edged past the intermittent spray and pushed off hard.

The octagonal room seemed to spin around her. She had to grab twice in order to grip a rubberized handhold, and still her body collided with the padded wall. I’ll never get this right! she thought as she fought to orient herself.

Sergeov pointed. “You think Ortho bureaucrats will do anything about this thing, do you?” he snapped ‘This?”

Virginia blinked. He was glaring at a graffito scrawled on the bulkhead nearest the grumbling axis bearings.

“Arc of the Sun,” he identified the symbol, bitingly. “The Kakashkiia bastards have followed us, even out here.”

“I’ve seen it before,” Virginia said softly. She felt a little short of breath over this unexpected sight. “Even in Hawaii . . .”

“So?” Sergeov interrupted snidely. “Even in Land of the Golden People? Even in your techno-humanistic paradise?”

Virginia’s brow knotted. Back in mission training she had taken a dislike to Sergeov, fellow Percell or no. He had spent nearly all his life in space—turning his physical drawbacks into assets in freefall—and yet every time she encountered him she felt uncomfortable, as if the man radiated long-suppressed bitterness.

She promised herself she would use her own computer to worm her way into the personnel files. She would see to it that they never shared a shift out of the slots during the seven decades ahead.

“Goodbye, Otis. I have work to do.” But he stopped her, seizing her arm.

“You know this is not first incident,” he said. “Only most blatant. Some of Arcists,” he sneered, “refuse to even talk to Percells aboard. They avoid us like we are xherobiy . . . unclean!”

Virginia shrugged. “Everybody’s been under a lot of stress lately. That’ll change when the habitats are completed, and once people have room to move around again. When we’ve unfrozen some folk from the slot tugs and get to look at some fresh faces for a change . . .”

Sergeov’s grip was iron-strong from years of hauling space gear around. “Might help symptoms,” he insisted. “But the disease goes on. You saw what Earth was like when we left. One after another of shlyoocha Hot Belt countries pass laws restricting our rights . . . rights of all genetically enhanced people!”

Virginia only wanted the man to let go of her arm. She tried reason.

“The nations of equatorial Africa and America have had a hellish century, Otis. I don’t like the specious turn their ideology has taken in recent years either, but at least they’re environmentalists, nowadays. If they’ve become a bit fanatical in that direction, well, anyone will admit it’s an improvement over the way their grandfathers behaved. The pendulum will swing back again.”

Virginia did not like the expression on Sergeov’s face. He looked at her as if she were pitiably, even criminally naive.

“You think so? But no, my dear young Percell. Is only the beginning! They are already at war with us!”

His unshaven face drew closer. “And who can blame them? When Homo sapiens awakens to what is happening, more and more repression will come against us—the Successor Race. Nothing less than future generations are at stake here!”

“Oh, come on, Otis. Virginia laughed dryly, trying to lighten the tone. “It’s not like we few Percells are the next step in evol—”

“No, you listen, girl!” Sergeov’s eyes narrowed. “This is the main reason for ail such paranoia, such persecution! Is hard to blame Neanderthals for trying to protect their obsolete form, after all. Species protect selves.”

He grinned severely. “But that does not mean we must let bastards squash us, either. Is up to us to act first, or perish!”

Even though they were clearly alone, Virginia quickly looked about. She did not want to be around if this seditious talk was overheard. With no wasted motion she used a judo grip-break to yank her arm away hard, sending the man spinning back. Sergeov bumped his head on the unpadded wall.

“Ow!” he protested in hurt surprise. “Yayatamiy! Govenka! What you do that for?”

“You Uber extremists don’t have the answer,” she breathed. “You only give Percells a bad name by talking like that. We aren’t Nietzsche’s supermen. We’re misunderstood human beings. That’s all!”

Sergeov grimaced, rubbing his head. “Ask the regular human beings, the Orthos, if they think us brothers,” he grumped.

Pushing the walls with her hands, Virginia backed away like a fish from a shark, even though Sergeov showed no inclination to follow her. Once down the hall a few feet, she spun about and kicked off down the dimly lit corridor toward her sanctuary.

Everything in Virginia’s private work capsule was neat, crisp efficient. The screens and opalescent holo displays that surrounded her webcouch all operated perfectly. Far from home and everything she had known—even hurtling out of the solar system at thirty kilometers per second—this was the center of her universe. She made certain everything was in good working order.

Officially, her role was to provide special support to Computations Section. But she had actually inveigled her way aboard this mission in hopes of getting some of her own research done. In the kind of scientific environment that was developing on Earth, the sorts of things she was interested in were frowned on.

Bio-organic computers . . . machines that might really think....These were areas that had been diagnosed as improbable, even dangerous, by increasingly conservative twenty-first-century science. Even in her native Hawaii, her superiors had grown more and more uncomfortable with the attention her work was drawing from the outside world.

But I know bio-organics can eventually outperform silicon and gallium! And machines can do better than moron mechanical water drawing and wood hewing. Stochastic processors can be made to think.

Over to the right, tucked under a desktop was the squat box containing her own, special simulation unit; the Kelmar organo computer had used up nearly all of her small personal-effects allowance, but it was worth it.

Panel lights rippled as the hatch hissed shut behind her and she slipped onto the web-couch. Virginia belted herself in and spoke softly.

“Hello, JonVon.”

The main holo screen glittered.

HELLO, VIRGINIA.

WILL IT BE WORK OR PLAY TODAY?

She smiled. No doubt in the eighty years ahead much progress would be made. It had to happen—even in a growing tide of scientific conservatism.

But right now her charge was the best there was—unconventional, using technology all but banned back home, but supreme in her own estimation.

She had named the unit after John Von Neumann, inventor of the theory of games. The program/mainframe could mimic a human’s response patterns well enough to pass a third-stage Turing test . . . fooling an unsuspecting person in a five-minute casual vidphone conversation into thinking the face and voice on the other end of the line were t

hose of a real person, not a computer.

JonVon could even tell a dirty joke, leering just enough and chuckling at the right time.

Unprecedented, yes. But stunts like that weren’t true “machine intelligence”—not the way Virginia felt should be possible.

The molecular hardware in that five-liter box should be good enough to model the complex standing wave in a human brain. She was sure of it. They didn’t agree back home, of course, and so it had never really been given a chance.

For the next few weeks she would have little time to engage in her private experiments. She had to use all her equipment, including JonVon, to supplement the ship’s mainframe Nearly all her energy was devoted to preparing those mathematical models Captain Cruz’s spacers kept demanding.

Later, though, during her years on watch, there would be time. Time for work and undiluted thought.

Back in the twentieth century, they knew how to have daring dreams, she thought. They did not believe in limits. It was one reason she liked old-time flat-screen movies . . . and enjoyed simulating old-time film stars and long-ago poets.

Those people nearly wrecked the world with their greed, but they did believe in ambition. They wouldn’t have rested until they had machines that could think.

She glanced at the timepiece etched indelibly under her left thumbnail. “How about twenty minutes of diversion, Johnny?” Virginia lifted a cable from the console and bared a whitish bump at the back of her head. When the connection clicked home, the symbols on the screen were accompanied by a rich voice inside her head.

POETRY, VIRGINIA?

She answered quickly with an impulsive thread of verse:

Ka Honua

—Earth, my home,

E hoomanao no au ia oe

—I shall remember you.

I wonder what he likes

to do,

And if he can spare me

the time of day’?

The line to her acoustic nerve hummed

MIXED STYLES, VIRGINIA?

DOES THE SECOND PART APPLY TO LOVE?

She blushed. “Oh hush, silly. Come on now. Let’s take a look at your conversation subroutines.”

CARL

The dusty ice sheets were speckled and splashed, rainbow-mottled, packed and scoured.

Carl Osborn spun his workpod and vectored down toward Halley Core. He flew away from the razor-sharp dawnline, aiming for the north pole where their base was finally taking shape.

The grainy gray and brown surface was changing rapidly now. Like tiny, fat ants, mechs moved over it, preparing docking areas and mooring towers. Spiders hammered holes into the ice, their endless microwave zzzzzzttts leaking faintly into some of the data channels. Carl muttered a quick correcting command to his suit’s comm filter control and the interference stopped.

Shaft 3 was nearly finished, a yawning pit like a dead eye socket. The first group of sleep slots would be going down that way soon. A kilometer of sheltering ice would shield the sleepers from the fatal sting of cosmic rays and the sleeting solar storms.

Random gouges surrounded the shaft. Discharging mech fuel cells had pitted the crusty ice. Broken gear lay where teams had dropped it. Chem spills had condensed into powdery green and yellow splotches. Discarded girders and sonic cartridges and shockjackets lay everywhere. What mankind would study Carl thought wryly, he first messes up.

Just barely visible over the curved horizon, now slowly coming into view along the dawnline, were the black gas-suppression panels. They were an ongoing experiment, armored against the high velocity dust streams and designed to generate electricity from sunlight. Their shadows reduced the outgassing from one-eighth of Halley Core’s surface, introducing an asymmetry in the boiloff. The panels could be turned so that they trapped heat, too, increasing the outgassing on the night side of the core. The net effect was a faint, persistent push that could alter the comet’s orbit, given time.

Or so the story went. To Carl the big black panels had been one solid week of grunt labor. They were too delicate to let the mechs do more than hold them in place, while he and Lani Nguyen and Jeffers had mounted them to the robo-arms that would turn them. The astroengineers were still tinkering with the gimmicks piling up data to analyze during the long outbound voyage.

It was hard to tell what was an intentional experiment and what was yesterday’s garbage. He wondered how messy Halley Core could get. In nearly eighty years they might thoroughly trash even this much ice.

Carl could see a thin black stripe coming out of shadow at the dawnline—the polar cable. It wrapped around Halley Core, pole to pole, and joined the equatorial cable at a perfect right angle, but separated by several meters for safety. The rails provided swift ways to zip around the surface. Still, Carl seldom used them. He liked to get free of the bleak ice, swim in serene blackness above it all.

Between him and the slowly spinning, potato-shaped iceworld were the swarming mechs he supervised. He thumbed instructions into his lap console, muttering code phrases automatically, making the distant dots turn their burden—a huge orange cylinder. Its smooth sheen reflected glinting sunlight.

—Channel D to Osborn. Real pretty, uh?—Jeffers sent from below.

“Well .....”

Awful color, he thought. And it’s the inner-corridor lining. We’ll have to look at it for seventy years.

The mechs dropped lower, angling the cylinder for Shaft 3, following his instructions. The potato-like shape of Halley Core revolved every fifty-two hours, just fast enough to make readjustment necessary as they approached. Subliming gas still rose from some of the active patches the scientists called “Sekanina-Larson” regions, making visibility hazy and creating a hazard of high-velocity dust. The thin fog blurred images at this distance—8.3 kilometers, his board said-and made it hard to use his automatic aligning program.

He had backup on the Edmund, in case of a malf. Fine, in theory. But by the time he got somebody online, the mechs might dutifully try to stuff the cylinder into a hill of ice. Despite Virginia’s earnest faith, computers could do only so much. From there on you had to eyeball it.

“Bringing it in slow,” he sent.

—Looks vectored up just a hair. Two clicks too high along the local y-axis,— Jeffers replied.

Carl looked down, recalibrated, saw that Jeffers was right. “Damn.”

—You okay?—

“Yeah. Just keep those beacons going.”

The four laser aligners bracketed Shaft 3 clearly, and Carl turned the mechs into configuration using the bright markers. A touch of delta V, a compensating torque. His board approved the shift. Good. But now the irregular ice was looming fast, and—

Gravity. He’d forgotten the damn gravity. Halley Core had only a ten-thousandth of Earth’s pull.....but in his half-hour decent from the solar-sail freighter the momentum had built.....slow but steady.....He punched in a correction, watching the equations ripple across his board.

Lights flashed red. “I’m braking;” he sent, and fired the mechs’ retros.

Damn the gravity anyway. Carl had been at Encke, worked around the rocky comet nucleus for weeks. It had been just like any deep space work—sometimes almost an elaborate waltz, smooth and sure, and a lot of grunt and sweat at crucial moments. Still, it was basically easy if you watched that your vectors matched, didn’t push anything except at its center of mass, worked steadily, kept your head.

But Encke was a runt. An old prune of a comet, broiled by its long stay in the inner solar system. Halley had a lot more mass, mostly ice. On the surface you never noticed the slight tug, but coming in like this, taking your time to aim carefully, that ten-thousandth of a G could add up.

The mechs’ blue jets fanned against the backdrop of ice, slowing the cargo. Carl saw suddenly that it wasn’t enough. The ponderous, hundred-meter-long cylinder was coming in too fast.

He ordered the lower portwise mech to turn and thrust at full bore. The unit spun, fired its reserve.

—What t

he hell you— Jeffers began.

“Clear the shaft!”

-What—

“Clear it!”

Standard procedure was to bring cargo to rest about fifty meters out, then nudge it in. His board said that was impossible. Instinct told him to try for something else.

He jetted forward, nearly caught up with the cylinder. A touch from the lower starboard mech, two quick torques here, a jolt sidewise to line her up—

An arrow from on high, aimed at a puckered black circle.

The orange cylinder struck the lip of Shaft 3, slowed—broke off an edge of ice—and drove on in, scattering flakes off into space.

Bull’s-eye, he rejoiced as the cylinder disappeared within the hole.

Jeffers cried out, —Hey! What’s the idea?—

“She got away from me.”

—Hell she did! You’re showin’ off, is all.—

Carl pulsed his own jets and landed easily, feet down. “Don’t I wish! Nope, I just corrected at the last minute. Figured it was better to try for a clean hit than to burn fuel decelerating. Especially since I couldn’t stop it anyway.”

Jeffers shook his head, exasperated. —Show-off,—he insisted, and went to check for rips in the material.

There weren’t any. Slick and snag proof, fiberthread could wriggle around sharp edges, which made it good for lining the snaking tunnels inside Halley Core.

The fifteen members of the Life Support Installation Group had ten days to honeycomb a fraction of the north polar region, line the shafts and tunnels with pressure-tight insulation, then flush it with air. Not long enough. And all that time the newly awakened scientists aboard the Edmund would be chafing.

Heart of the Comet

Heart of the Comet